The IVF Pioneers: Who Really Wrote Their Autobiography?

This blog post is about the author’s recent paper in Medical History, The ghostwriter and the test-tube baby: a medical breakthrough story

For 45 years A Matter of Life has provided the standard account of the science and medicine behind the sensational birth of the first ‘test-tube baby’. Now the ghostwriter of this joint autobiography of geneticist Robert Edwards and gynaecologist Patrick Steptoe has finally told all. Or rather, his archive has revealed that he rewrote the book in ways that have shaped the history of IVF (in vitro fertilization) to this day.

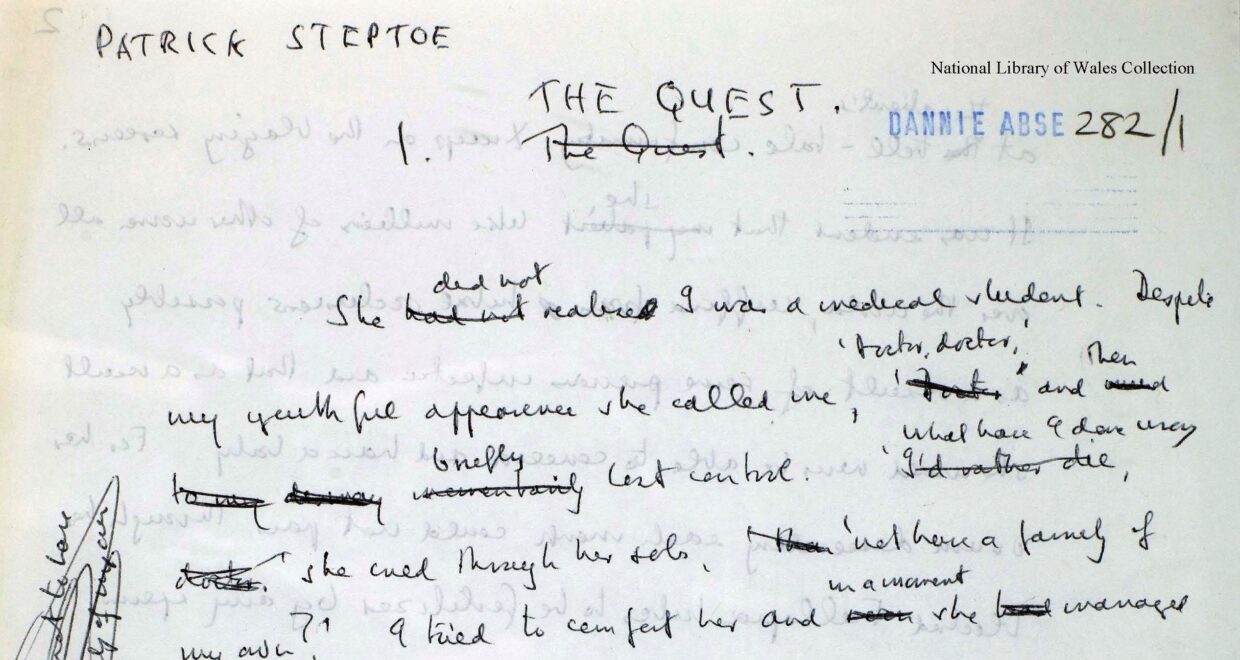

I entered that archive in February 2023, when I spent a week in Aberystwyth walking each morning from the seafront up Penglais Hill to the National Library of Wales. I had come there because documents in the Edwards Papers at Churchill College, Cambridge hinted that the Cardiff-born physician and poet Dannie Abse changed more than anyone had imagined based on brief thanks. The publisher’s archive confirmed that Hutchinson, which had bought the inside story of the ‘baby of the century’ and needed a bestseller, hired Abse to rework the authors’ disappointing draft.

Abse’s ‘ghostwriting’ folders disclosed a major transformation and allowed me to reconstruct the collaboration. Now, the very idea of collaborative autobiography might sound strange. Are not subject, author and writer supposed to be one and the same? But when a commercial project needs to engage readers and the author lacks time or skill, a ghostwriter may be employed in science and medicine as in politics and sport.

Rare in this case, and exciting, was the richness of the evidence about the process. I tracked revisions as Abse reorganized the authors’ blow-by-blow account into engaging chapters. I identified strategies such as using interviews to condense exposition into vivid scenes with characters and dialogue. As I sat in the long, tall reading room and later, when I reviewed well over a thousand photos of pages, how the collaboration changed the narrative gradually became clear.

Edwards came late to the project of alleviating infertility, but Abse adjusted the text so that it appeared as a career-long quest. Since the public profile of infertility was then low, he highlighted the distress it caused and presented Edwards’s embryology as always aiming to relieve this.

Abse gave women—wives, assistants, patients—larger roles in the drama. This was less feminism than a consequence of fleshing out characters so that readers could relate. He made the whole book open with the cry of an infertile patient I suspect he invented. He then ensured that ‘test-tube mother’ Lesley Brown was introduced as a person rather than, as in the initial draft, through laboratory procedures on her embryo. This let readers feel the emotion when, at the end, Steptoe handed her the baby she had been told she would never have. One ‘hardbitten journalist’ was reduced to tears, an effect unlikely without Abse’s rewrite.

Meanwhile, I came across Abse’s reflection that autobiography—he also wrote two of his own—‘buries the real life’ by altering, obliterating and accentuating in the service of insight and pleasure. It is trickier to bury others’ lives and have the result ring true. That problem led to some tensions in an otherwise amicable partnership. Abse, a lapsed Jew who attended a Catholic school, introduced biblical references. Edwards, an atheist, objected, ‘Danny This isn’t me!’ but was overruled. Yet he and Steptoe came across more sympathetically, and IVF was promoted more effectively, than in their own draft.

It surprised me that the authors did not have the final say, but that was the price of getting their message out (and earning higher royalties). The commercial imperative is more obvious in Joy, last year’s Netflix film, which altered A Matter of Life to emphasize the role of Edwards’s technician Jean Purdy. Yet Abse began that reassessment and, as I show in my paper, through the ghostwriter the market moulded historical writing on IVF right from the start.