The roots of honour: babies’ ‘struggle for recognition’ in Greek literature and thought

Can babies have honour? Can they be recognised as agents? And can they take part in dynamics of recognition? If we consider ancient Greek sources, both literary and philosophical, we can get a positive answer to these questions – an answer that strikingly converges with what developmental scientists tell us about babies’ psychology. Indeed, recent experiments have revealed that babies are capable, soon after they are born, to engage in bidirectional recognition with adults. Babies expect adults to recognise them by adequately responding to their emotions, and, when adults fail to do that, babies will manifest their upset with visual cut-off. In other words, babies have an embryonic form of what the Greeks would have referred to as timē, a word that captures all forms of interpersonal recognition, such as respect and esteem.

This helps on the one hand to explain an intriguing scene in the Histories of the Greek historian Herodotus (half of the 5th century BCE) and on the other to appreciate more fully some passages in the comedies of the Greek poet Menander (second half of the 4th century BCE). Cypselus is well known as the cruel tyrant of the Greek polis Corinth in the Archaic period. Less known is the fact that, according to Herodotus, he saved his own life by smiling to the men sent to kill him when he was a baby. By smiling at him, the baby gives recognition to the man who was about to kill him, who is thus urged to recognise the baby in his turn – obviously making it much more difficult to kill him. The episode thus vividly illustrates emotional alignment between babies and adults and its implications for babies’ honour, namely an intuitive understanding of their claims to recognition.

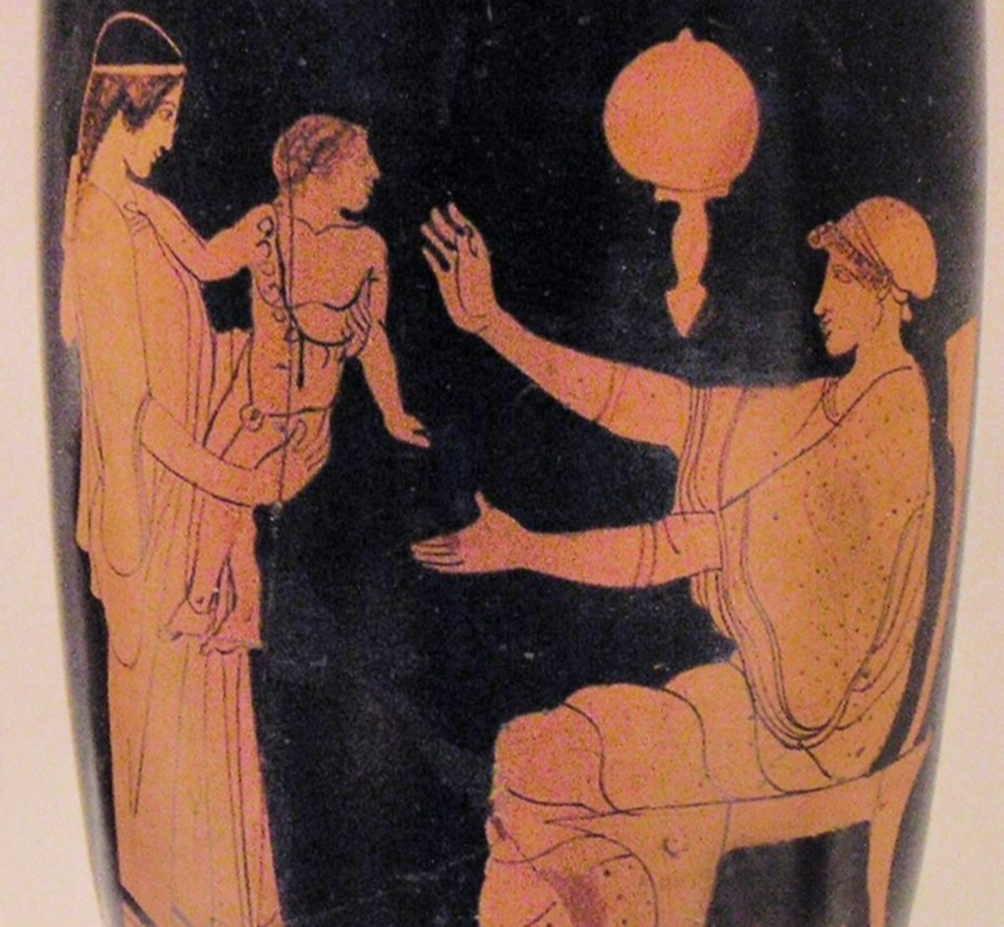

Menander’s comedies provide other examples of recognition and respect towards babies. In one scene, two slaves quarrel about who should keep the objects that were lying together with a foundling baby: one of the slaves claims that the objects must stay with the child, in so much as he is a human being and should not be deprived of what belongs to him. The slave also insists the baby himself is an agent, and presents him to the Athenian citizen acting as an arbitrator so that the latter might more easily feel the responsibility to respond to the baby’s implicit demand for justice.

Philosophers like Plato and Aristotle also recognise that babies have claims to recognition. Plato, in particular, stresses the importance of bringing up babies correctly since the very beginning to ensure that they develop an appropriate timē, namely a sense of their own value and standing vis-à-vis those of other. To put it in philosopher Axel Honneth’s words, babies are involved in a struggle for recognition. As I argue more extensively in my piece on The Classical Quarterly, Greek literary and philosophical texts reveal a clear awareness of babies’ incipient sense of honour and their participation in dynamics of bidirectional recognition.

Read the associated research, out now open access in The Classical Quarterly: