Cuerpo, mestizaje y colonialidad: La alteridad de las mujeres trans en las muestras fotográficas Padre Patria y Vírgenes de la Puerta/

The photographic series “Padre Patria” (2014) and “Vírgenes de la Puerta” (2014), by Juan José Barboza-Gubo and Andrew Mroczek, offer a visual narrative of hate crimes against the LGBTI community in different parts of Peru. This article highlights the political dimension of this photographic project and its dual purpose. On one hand, it makes visible the experiences of marginalization and violence suffered by trans women. On the other hand, the use of photography helps to subvert the heteronormative order that produces and reproduces practices of marginalization, invisibility, and violence. The main goal of this article is to rethink the identity of trans women from the perspectives of sexuality, mestizaje, and the coloniality of power as markers that have regulated and modified bodies, but at the same time destabilized and transgressed the patriarchal, racial, and heteronormative order.

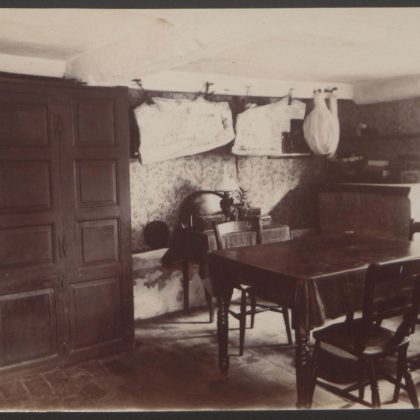

I argue that the photographs in “Padre Patria” depict marginalized spaces where hate crimes occurred to show the victims’ vulnerability that not only arises from the fact that they present a challenge to heteronormative sexuality but also confronts the viewers with racialized victims who live in spaces of extreme poverty and abandonment. In this way, the visual representation is exceeded by not showing the bodies of the victims. This photographic series allows us to reflect on how LGBTI victims can be configured and conceived, as their bodies constitute a dual presence/absence, which invites us to evoke the suffering and attacks committed through the constitution of a disembodied image.

In “Vírgenes de la Puerta”, I explore the otherness in trans women’s sexuality through religious iconography as a form of resistance. This otherness, which I understand as another way of viewing femininity, is evident in the choice of models with Andean descent that reveal part of their anatomy, such as breasts, buttocks, long hair, etc. These parts highlight feminine features that contrast with the old mansion in which they are portrayed. The ruined mansion and the incorporation of religious elements, such as crowns, veils, capes, skirts, and the use of an altarpiece, convey the coloniality that persists in the formation of national identity. The portraits challenge the machismo and Marianismo prevalent in religious and national thought. Within this conceptualization, the figure of the woman is mediated by the figure of the Virgin, who symbolizes the maternal element associated with the nation and the homeland, along with certain values that must prevail, such as purity, self-denial, and the likeness of perfection and good behavior before Christ.

Finally, this article delves into the political exercise of photography as a dynamic space that exceeds the limits of the state and institutions of power. Photography goes beyond the aesthetic configuration of portraiture and serves to denounce hate crimes by breaking down the division between the private and public spheres and showing the struggles of the LGBTI community in Peru.

The article, Cuerpo, mestizaje y colonialidad: La alteridad de las mujeres trans en las muestras fotográficas Padre Patria y Vírgenes de la Puerta by Rocío del Águila Gracey is published in the Latin American Research Review.