What wild monkeys in The Gambia can teach us about intestinal parasites (and why it matters to us)

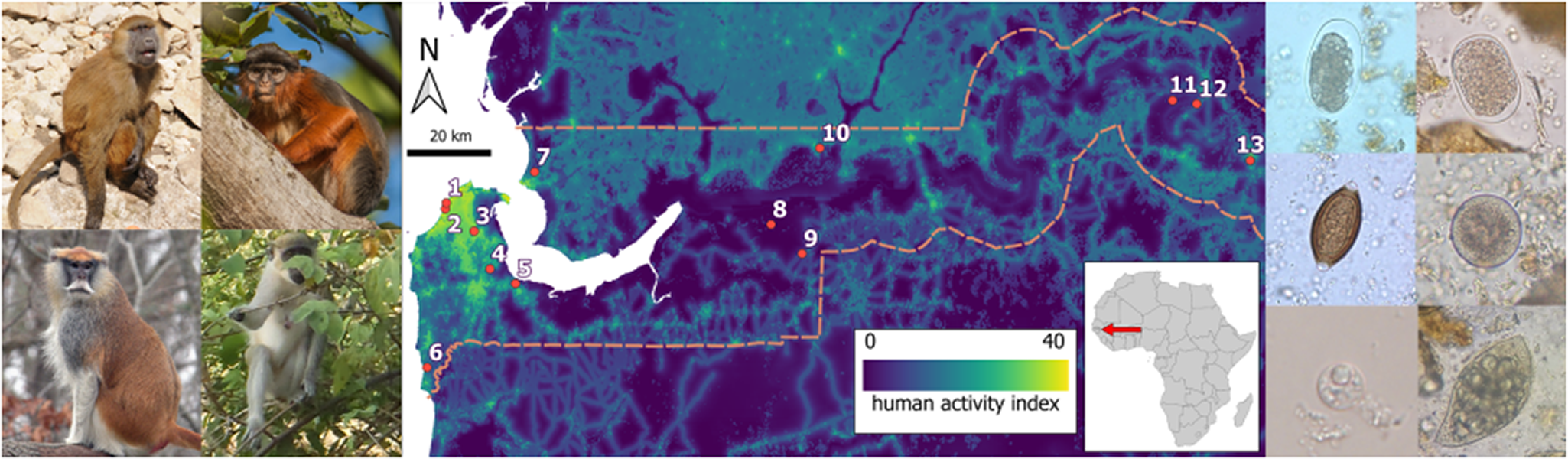

The latest Paper of the Month for Parasitology is Intestinal parasite infection in non-human primates from The Gambia, West Africa, and their relationship to human activity and is available open access.

If you stroll through The Gambia’s forests you might glimpse four very different monkeys: the green monkey, patas monkey, Guinea baboon and the endangered Temminck’s red colobus. This research followed those primates for three field seasons, collecting fresh droppings (not glamorous, but highly informative!) to ask a deceptively simple question: does living closer to people change the parasites these monkeys carry?

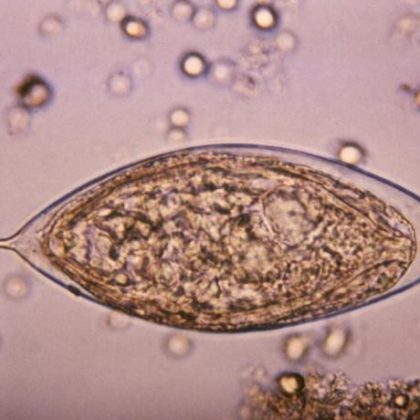

A surprisingly rich parasite zoo

From 99 faecal samples we identified 21 species of intestinal parasites – everything from common worms to various protozoa and amoebae. Overall, seven in ten monkeys harboured at least one parasite, and Guinea baboons averaged nearly three different species apiece.

Yet when we crunched the numbers, two expected risk factors didn’t matter: the amount of human activity around a troop (measured with a high-resolution “human footprint” map) and the size of the group itself. In other words, despite decades of deforestation and villages pushing up against remnant forest patches, parasite diversity in Gambian monkeys looked much the same in busy tourist zones as it did in remote savannah.

Why that result matters

- Conservation insight – Red colobus, our most arboreal species, carried the fewest parasites. Protecting canopy corridors may therefore benefit both primate health and biodiversity.

- Ground truth for global assumptions – Prior studies in Kenya showed higher parasite loads in fragmented habitats; our contrasting result highlights that ecological context matters. One size does not fit all ecosystems, so large-scale generalisations should be made with care.

Take-home message

Even in landscapes reshaped by people, parasite ecology can defy expectations. By mapping the hidden “parasite worlds” of monkeys, we gain clues about environmental change, zoonotic spill-over, and how to safeguard both wildlife and human communities.