From Ancient Latrines to the SDGs: The Undeniable Importance of ‘Safe Toilets’ in Parasitic Disease Control

Parasitology are Celebrating World Toilet Day 19th November 2024

Those that study parasitic diseases, particularly the soil-transmitted helminthiases and/or giardiasis, know that the enduring theme of the toilet and sanitation typically conjures up serious academic debate. For others less familiar with faecal-oral transmission of human parasites, it simply conjures up a common source of cultural amusement, perhaps even embarrassment too. Despite “toilet humour,” the importance of the humble lavatory is undeniable; without functional toilets and adequate sanitation, today’s global public health would be very different. Yet still innumerable people suffer daily shame, stigma, and illness due to being unable to access properly functioning and sanitary toilets.

Despite being a specific target within the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG6), it is still a sad fact that access to “safe toilets for all by 2030” is out of reach for hundreds of millions of people across the world. Why does it remain so? Amongst several reasons, conflict, extreme weather events, and other disasters either individually or collectively destroy, damage, or disrupt functional sanitation services. Similarly, the infrastructure costs of installing sufficient household or communal toilets are not trivial, as well as the associated waste water handling systems. Toilets are an essential minimum in the strive towards ending open-defecation and open-urination.

We acknowledge, and have previously celebrated, the importance of hand-washing within the repertoire of safe sanitation. Today, we illustrate how Parasitology also has a supporting role in advocating “World Toilet Day”. We have assembled a brief collection of 5 papers that reveal often overlooked dimensions and implications of the toilet and communal latrine. This is with specific regard to its role in parasitic disease surveillance and control through time.

Take a minute to ponder all those parasites found in ancient latrines as far back as the 6th Century 7th–6th century BCE, that give a fascinating insight into past lives when whipworm, roundworm, and protozoa parasites that cause dysentery were rife. multi-seat public latrines of Roman times were not sufficient to keep helminths at bay. Still, these parasites are not a problem of the past. Consider how today’s inadequacies of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) cause widespread disease, and in particular blight childhood development blight the lives of millions of children.

Through World Toilet Day, we should look forward to a future world when safe toilets are a reality for everyone.

Parasites in toilets through time

1. A comparative study of parasites in three latrines from Medieval and Renaissance Brussels, Belgium (14th-17th centuries). Graff A, Bennion-Pedley E, Jones AK, Ledger ML, Deforce K, Degraeve A, et al.

2. Human parasites in the Roman World: health consequences of conquering an empire. Mitchell PD.

3. Giardia duodenalis and dysentery in Iron Age Jerusalem (7th-6th century BCE). Mitchell PD, Wang TY, Billig Y, Gadot Y, Warnock P, Langgut D.

Inadequate WASH and soil-transmitted helminthiases

4. Ascaris and hookworm transmission in preschool children from rural Panama: role of yard environment, soil eggs/larvae and hygiene and play behaviours. Krause RJ, Koski KG, Pons E, Sandoval N, Sinisterra O, Scott ME.

5. Soil-transmitted helminthiasis among mothers and their pre-school children on Unguja Island, Zanzibar with emphasis upon ascariasis. Stothard JR, Imison E, French MD, Sousa-Figueiredo JC, Khamis IS, Rollinson D.

To view all the papers in the collection, click here: ‘Parasites in toilets through time’.

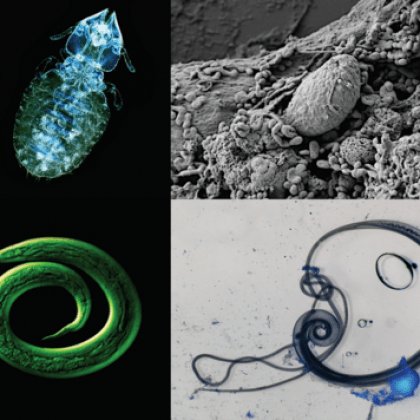

A peculiarly human invention – the flushing toilet (left) – which helps break the transmission cycle of many parasitic worms that rely on faecal-oral transmission by confining the eggs and larvae such as the embryonating strongyloidid depicted (right).