Bibles and Bible Translating in Early Modern England

There are some 6 billion bibles circulating across the globe and a further 100 million printed every year. Each of these copies, from the children’s illustrated editions to the grandly bound King James Bibles, make a claim to be the textual and material expression of God’s Word: the Word made Book. The 6 billion bibles in circulation all differ in their language and format but they also often translate the same word out of the original Hebrew and Greek in different ways. The Bible is the principal authority that guides Christian life and the Church but there is not one bible but many. What are the effects of multiple translations coexisting on the Church, religious identity, toleration and practice?

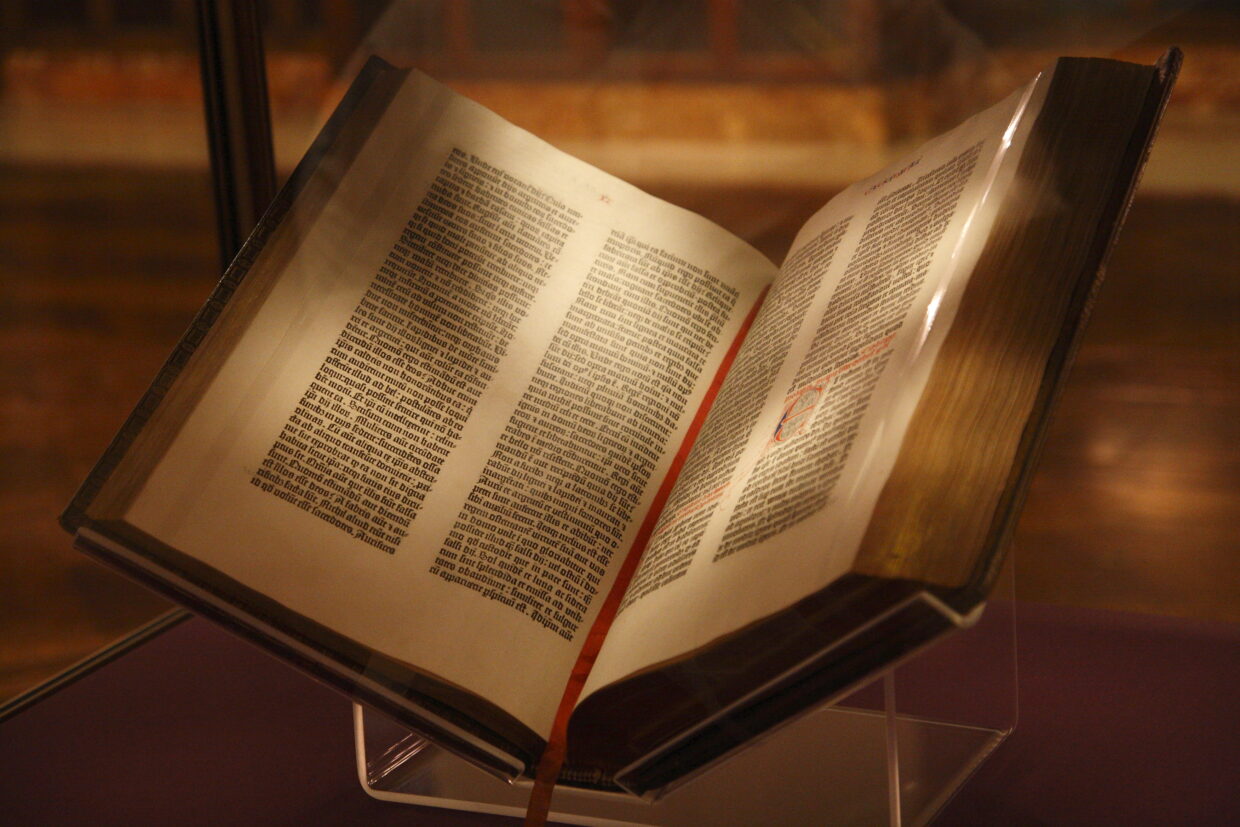

These questions are not new. Multiple manuscripts of the Hebrew and Greek texts which form the Bible coexisted with each other from the earliest days of the Jewish and Christian traditions and then, throughout the medieval period, a whole range of manuscript bibles were produced. It was the invention of print and the Reformation – the processes by which Protestantism developed and the hegemony of the Catholic Church in Europe ended – which brought about a wave of new translations and printed Bibles. The 1500s witnessed, in the English language alone, over a dozen distinct translations of the Bible and many variants of each of these. The printing press enabled these translations to exist in greater numbers and reach a greater audience. This was heightened by the Protestant Reformation’s emphasis on people reading the Scriptures in their own language.

Protestants in Elizabethan England were thus surrounded by many different translations of the Bible. This was a situation which had developed organically but which had profound impacts on the religious and political landscape in Britain. While many scholars saw practical and intellectual advantages to what I have termed ‘biblical plurality’ (multiple bible translations circulating simultaneously), a growing number of voices believed that enforcing one uniform translation of the Bible would provide stability and slow the growing divisions within the Church.

Into this landscape, the Catholic scholar and translator of the Bible, Gregory Martin (c.1542-82), launched an attack on the English Protestant use of multiple translations, alongside his own translation of the New Testament into English. Gregory accused English Protestants of ‘hopping’ between different translations to help defend their ever-changing religious policies and he charged them with heresy and hypocrisy for their treatment of biblical texts. William Fulke (1538-89), master of Pembroke College, Cambridge, was commissioned to refute Martin’s arguments and spent the years 1582-89 completing a series of works which defended English Protestant bibles. Fulke had the unenviable task of defending biblical plurality whilst refuting Martin’s own translation of the New Testament into English which had been produced to support Catholic belief and practice.

The exchanges between Martin and Fulke have not been subject to in-depth exploration and my article ‘Debating Biblical Translation in Late Elizabethan England’, with The Historical Journal,explores what these exchanges show us about the processes of bible translation in early modern Europe and how Protestants came to understand, and even defend, the culture of biblical plurality which had developed in England. Prior to the great attempt to bring about biblical uniformity in the form of the King James Bible of 1611, we can see in these debates how Fulke had to first make sense of the biblical landscape which surrounded him in order to even begin to defend it.