Spreading the Revolution: Paine’s Rights of Man in Germany

Tom Paine’s revolutionary Rights of Man, whose first part was published in London in 1791, was an extraordinary publishing success and extremely influential. That applies far beyond Britain and my article explores its echo in Germany.

The central character in the story is Meta Forkel, whose translation of Rights of Man was published at Berlin in 1792. In addition to her language skills, Forkel’s political sympathies made her a likely accomplice in the dissemination of Paine’s work. She was part of the Jacobin circle around Georg Forster at Mainz and would even be imprisoned for several months after the forceful dissolution of the Mainz Republic in 1793. It was certainly no coincidence that Forkel translated Rights of Man and other radical works.

When the Berlin publisher Christian Friedrich Voß proved reluctant to publish Rights of Man (as had Paine’s original publisher), Forkel urged him to do it despite possible dangers. Upon seeing the book, she told Voß, he would not be able to resist printing it, ‘even if it was charged with high treason, and of course it’s high treason to tear down the consecrated idols of many centuries’. When apparently no reply was forthcoming, she submitted the manuscript to the printer anyway. Voß finally came around and the book was published. This episode powerfully demonstrates the translator’s initiative and reminds us of the factor of contingency; it is only due to Forkel’s commitment that Rights of Man appeared in German.

Forkel not only provided a faithful translation of Paine’s English text that was hailed by contemporary reviewers and still reproduced by the prestigious German publisher Suhrkamp in 1973, but she also made an important addition by supplementing the French Constitution of 1791. Forkel referred to it as a ‘charter of human freedom’ and accorded it world-historical significance. Presumably, adding the Constitution was so important to her because nothing comparable existed in the German states and she hoped it might serve as an inspiring blueprint.

Forkel’s translation no doubt facilitated more widespread access to Paine’s work. Yet its impact in Germany was not only dependent on translation, as Paine’s ideas spread through other languages as well. Paine was an international celebrity and his work became very visible in Germany during the 1790s. German intellectuals read his works in the original or in French while reviews popularized his ideas or opposition to them. Accordingly, the story of Paine’s impact in the German-speaking parts of Europe involves a rather disparate group of actors, not least several detractors whose criticism unintentionally helped to spread his ideas further.

The generally accepted view is that Paine’s reputation soon became tarnished by the anti-Christian Age of Reason, which was also translated into German. But worries about his influence in both religious and political matters evidently persisted amongst his opponents. After all, Paine’s declared aim was to spread revolution. What is more, he described despotism as the German principle of government and, in his dedication of Rights of Man, Part Two explicitly expressed hope for the liberation of Germany. And Paine’s writing proved popular and effective. The Jacobins of Altona, for example, explicitly commended Rights of Man in a pamphlet that called for revolution. Undoubtedly, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that Paine’s work deserves a more central place in future scholarship on the Revolution debate in Germany.

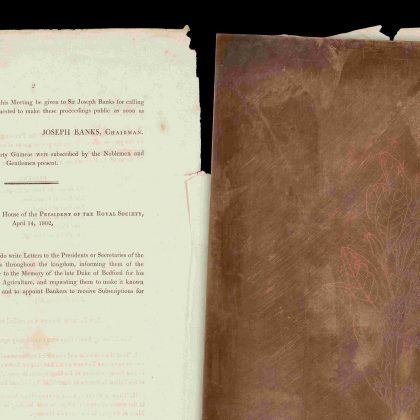

Image: Wha wants me © The Trustees of the British Museum, released as CC BY-NC-SA 4.0