The Rise of the College Degree as Workforce Gatekeeper

This accompanies the History of Education Quarterly articles How Austerity Politics Led to Tuition Charges at the University of California and City University of New York by Jennifer M. Nations and The Right to Residency: Mobility, Tuition, and Public Higher Education Access by Camille Walsh

Many Americans have come to accept that to obtain a white-collar job in the United States today, a bachelor’s degree is essential. This hasn’t always been the case. In previous centuries, businesses took on apprentices, children learned family trades, and companies trained their workforce on the job. In contrast, companies today expect prospective employees to arrive at their doorsteps with the requisite skills. Unfortunately, this system doesn’t work for all Americans. As two scholars have demonstrated recently in the pages of History of Education Quarterly, the college degree has become a kind of workforce gatekeeper, privileging only those students able to pay tuition, satisfy state residency laws, and devote four years to higher education.

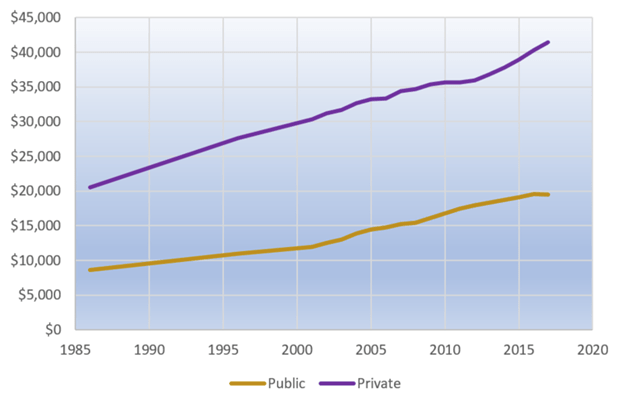

Increasing tuition costs for higher education have rendered the college degree more inaccessible for students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. As Jennifer Nations shows in “How Austerity Politics Led to Tuition Charges at the University of California and City University of New York,” states began to increase tuition at public universities in the second half of the twentieth century. Prior to the 1960s, states viewed low-cost access to higher education as a public good. However, as the economy took a turn in the late-1960s, so did the push to decrease public funding for higher education. Government contributions began to decline, and so did funding for Intuitions of Higher Education (IHEs). In response, colleges and universities had to turn to tuition streams to support the cost of funding their institutions.[i] The result has been an increased burden on students to fund their college experience while states continue to cut back on their contribution to higher education.

Figure. Source: National Center for Education Statistics, “Tuition Costs of Colleges and Universities, 1985 to 2019,” https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=76. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

State funding for higher education has been on the decline since 1991, yet the cost of tuition has doubled. Access to federal aid is also on the decline. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in the 2018-2019 school year only 32.9% of undergraduate students received federal student loan funding, the lowest percentage seen in during the prior decade. Between 2007-08 and 2017-18 tuition costs at public institutions steadily rose by 31 percent while the average dollar amount of federal student loans received by students decreased.[ii]

In response to rising tuition rates, many students seeking a high-quality, affordable public university education have sought entrance to institutions outside the states where they reside, with mixed results. As Camille Walsh demonstrates in “The Right to Residency: Mobility, Tuition, and Public Higher Education Access,” state residency laws have served as an important barrier for individuals seeking to improve their circumstances by moving toward new opportunities in different parts of the country. Public institutions enroll most students in US higher education. A benefit of attending a public institution in one’s home state is a substantially discounted tuition rate. But state residency laws restrict mobility under the notion that tax dollars are to be used to fund public higher education for in-state residents. At the same time, the amount of state funding for higher education is on a continual decline. Thus, residency policies continue to limit the access of out-of-state students to public higher education, even as the rationale for their implementation is based on a funding source that is no longer a primary source of financial stability for public institutions.[iii]

Historically, politicians have viewed higher education as a means for producing a highly skilled workforce and bringing status and income to local communities, yet the political will to support this production has been on a downward trajectory for several decades. When higher education is seen as a private good, students are left with the burden of paying for their education. With the exception of Bernie Sanders and some of his fellow progressives, few political leaders have advocated for free or reduced tuition; the majority continue to shift the burden onto students and public institutions tasked with finding creative ways to keep tuition costs affordable. None of us knows precisely what will come of higher education over the next several decades, but historians have provided an important guide for understanding social norms and expectations in changing political contexts. IHEs need to work on putting the “public” back into public higher education. Those who believe in the value of a college degree should advocate for access for all students who want to learn, push for funding reconfiguration, and improved town- gown relations. Higher education leaders should take up this mantle and start working to showcase all the ways in which IHEs serve not only the local economy but also society on a larger scale.

[i] Jennifer M. Nations, “How Austerity Politics Led to Tuition Charges at the University of California and City University of New York,” History of Education Quarterly 61, no.3 (2021), 273-96.

[ii] National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/TrendGenerator/app/answer/8/37.

[iii] Camille Walsh, “The Right to Residency: Mobility, Tuition, and Pubic Higher Education Access,” History of Education Quarterly 61, no. 3 (2021), 297-319.