Looking for Women’s Learning in Medieval England

This blog accompanies Megan J. Hall’s History of Education Quarterly article Women’s Education and Literacy in England, 1066-1540

In 1420, a notary public named Master Peter Church apprenticed two orphaned English sisters named Alice and Matilda Shaw. The seeming mundanity of this occurrence obscures an important consideration. If the Shaw sisters were to work for a notary, would they require literacy? Or were they literate when Church decided to employ them? Megan Hall’s “Women’s Education and Literacy in England, 1066-1540” draws on a range of primary and secondary sources to explore the ways women like Alice and Matilda Shaw learned, examining the transmission of knowledge in a variety of formal and informal contexts throughout the medieval period. Hall’s article challenges historians to look for women’s learning well before the early modern period in a variety of unexplored contexts, expands historical understanding of the intellectual lives of women in the medieval world, and elucidates the extent to which important avenues of education existed outside of formal or elite institutions.

The study of women’s medieval learning is a largely underdeveloped field. “Not a single monograph has been written surveying the history of medieval English schooling for girls,” Hall observes.[1] However, English women learned in a variety of ways. Some women learned basic literacy at local elementary schools, and, by the sixteenth century, schools served as training grounds for female teachers.[2] Girls “learned from the same tools as boys” in the earliest phases of their education, while both young men and young women received training in social and behavioral deportment.[3] Hall notes how St. Margaret of Scotland was said to “occupy herself with the study of the Holy Scriptures and delightfully exercise her mind,” while saints and literary figures “Felice, Morgan, Viviane, and St. Katherine of Alexandria” all provided models of female education to readers and students alike.[4] Nunneries doubled as another arena for women’s literacy training, and Hall concludes that historical, institutional, and fictional examples indicate the prevalence of discourse and conversation surrounding female education in medieval England.[5] Women like St. Margaret of Scotland and her daughter Matilda studied scripture, learned Latin, and developed their own wealth of knowledge in spiritual and intellectual pursuits.[6] Hall concludes that access to a dynamic, literary, and intellectual education was not exclusively reserved for elite men in universities.

Non-elite women, alongside the “rising bourgeoisie, the merchant and artisan classes, and in some cases the peasantry,” experienced both a “practical and literary education.”[7] In households, women learned a variety of skills through predominantly oral instruction. Mothers were important literary and artistic facilitators of female education, as figures like St. Anne modelled moral and spiritual instruction.[8] Fathers and sons often coupled female and male education in the household. In the romantic verse Floris and Blancheflour, the king’s son, Floris, insists on being educated in reading and writing Latin alongside his female childhood companion Blancheflour—an account that proves neither “wildly exaggerated” nor altogether unlikely for many families.[9] The language of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century treatises, literature, and poetry concerning female education emphasized “appropriate behavior in religion, society, and marriage,” asserting the growing “bourgeois ethos” in the late medieval period.[10] Some families also turned to nunneries to educate their daughters as a means of spiritual, linguistic, and intellectual training.[11]

Beyond the household, the school, and the nunnery, laboring women also learned in medieval England. The poor had a greater need than elite or cloistered women to secure some form of professional training: “Whether it was brewing and selling, weaving, cloth-making, dyeing, baking, ironmongery, trade, shopkeeping, inkeeping, or innumerable other occupations, women began to acquire these skills in childhood,” Hall concludes.[12] Many girls were apprenticed or indentured in homes or workshops, and, in each pursuit, women received some instruction in the trade. Young girls may have received some initial literacy or basic professional training at home, while their apprenticeship taken on during pueritia prepared them for the trade they might practice in adolescentia.[13] “It is particularly important,” Hall observes, “to note that the skills we perhaps most associate with education in the modern age, reading and writing, were taught to some girls in these [working class] groups, especially when such skills were needed to carry out a trade.”[14] Significantly, women in non-elite settings engaged in what Steven Justice calls “recognition literacy,” which enabled often enabled working women to navigate French and English in the process of record-keeping or inventory.[15] Though laboring women probably received less training than apprentices, Hall notes that “[laboring] women would have been learning and training from an early age to prepare for homekeeping, directing or helping in agricultural labor, and any other needs of their anticipated future.”[16] For non-elite women, learning was a critical endeavor, whether they were preparing to make a living, support a family, or simply support themselves. To Hall, this represents a critical conclusion: differing but extant levels of literacy among women in medieval England suggests that access to knowledge was neither entirely stifled nor exclusively confined to their fulfilment of gender norms. Instead, Hall concludes, women engaged in a complex and multifaceted intellectual life throughout medieval England.

Whether they were trained to manage households, preserve families’ spirituality, embrace social and cultural norms, face the changing dynamics of a “bourgeois” sensibility, practice a trade, or perform manual labor, medieval women experienced education, and female learning was an important and determinative element of English society. Legal complaints, for example, reveal that people like William and Johanna Kaly petitioned for access to a female apprentice named Agnes Cook in 1376, despite her apprenticeship to a London cutler named Jusema.[17] Agnes’ education proved extremely valuable and competitive in the dynamic world of medieval England. Future studies of women’s history, learning outside of academic institutions, and the experiences of laboring and contingent classes would benefit from adopting the approach Hall has taken in extrapolating instances like these to illustrate larger trends. In uncovering a vast array of contexts in which women acquired knowledge, became literate, and promoted intellectual advancement, Hall has successfully amplified the archivally silent world of women’s education in medieval England.

Listen to Megan Hall discuss her History of Education Quarterly article on the HEQ&A podcast

[1] Megan J. Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy in England, 1066-1540,” History of Education Quarterly 61 (2021), 181, 183-85.

[2] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 205-06.

[3] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 188-90.

[4] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 188-89.

[5] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 190-91.

[6] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 188-89.

[7] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 183.

[8] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 191-92.

[9] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 196-97.

[10] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 193-94

[11] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 204.

[12] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 207.

[13] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 209.

[14] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 210.

[15] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 210.

[16] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 211.

[17] Hall, “Women’s Education and Literacy,” 210

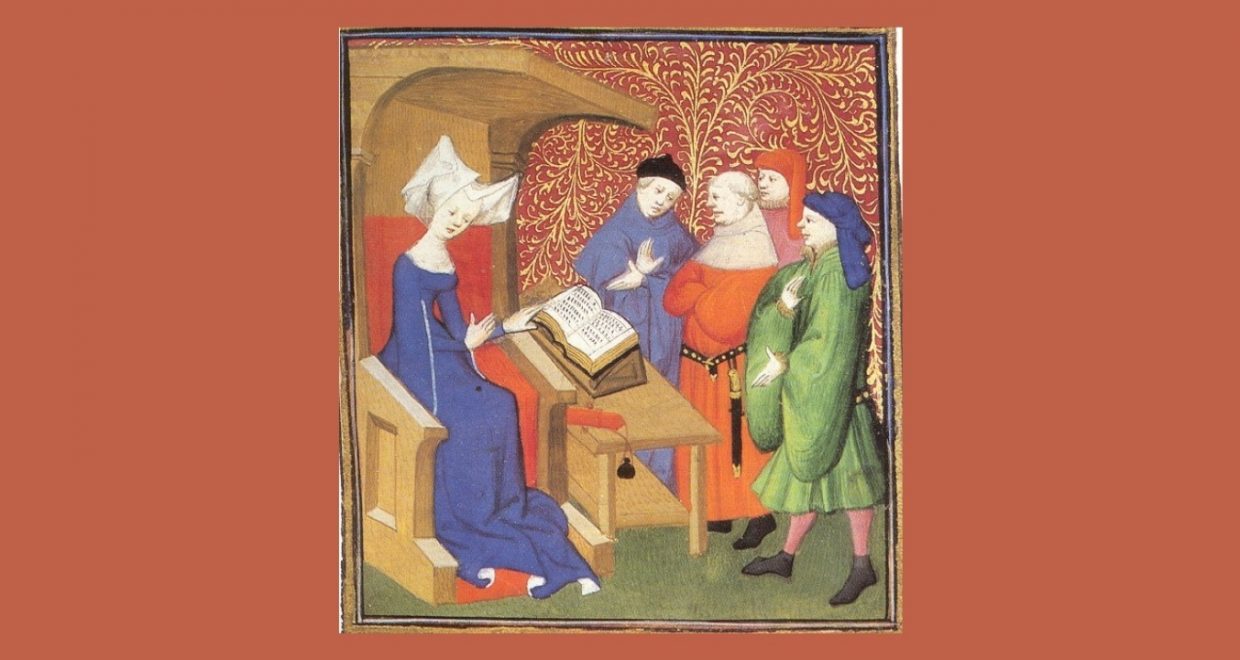

Main image: Christine de Pisan instructs her son, Jean de Castel.circa 1413