Extreme Justice: decapitation burials in late Roman Britain

In popular imagination, the Roman Empire was an agent of law and peace in the ancient world. However, Rome had a brutal side, with the death penalty used for a wide range of crimes. Records from the later Roman Empire refer to condemned prisoners being decapitated, burnt alive, or mauled by wild animals. Archaeological evidence for these practices, however, has been limited.

The discovery of 17 decapitated bodies by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit provided an opportunity to better understand the use of capital punishment in late Roman Britain.

Decapitated bodies are far from unknown in Britain: they account for 2–3% of Roman burials. However, most cemeteries contain at most one or two decapitated bodies, and the practice has usually been interpreted as a ritual, possibly associated with burial rites. The seventeen bodies excavated in Somersham, Cambridgeshire UK, are the largest concentration of Roman decapitations yet excavated in Britain.

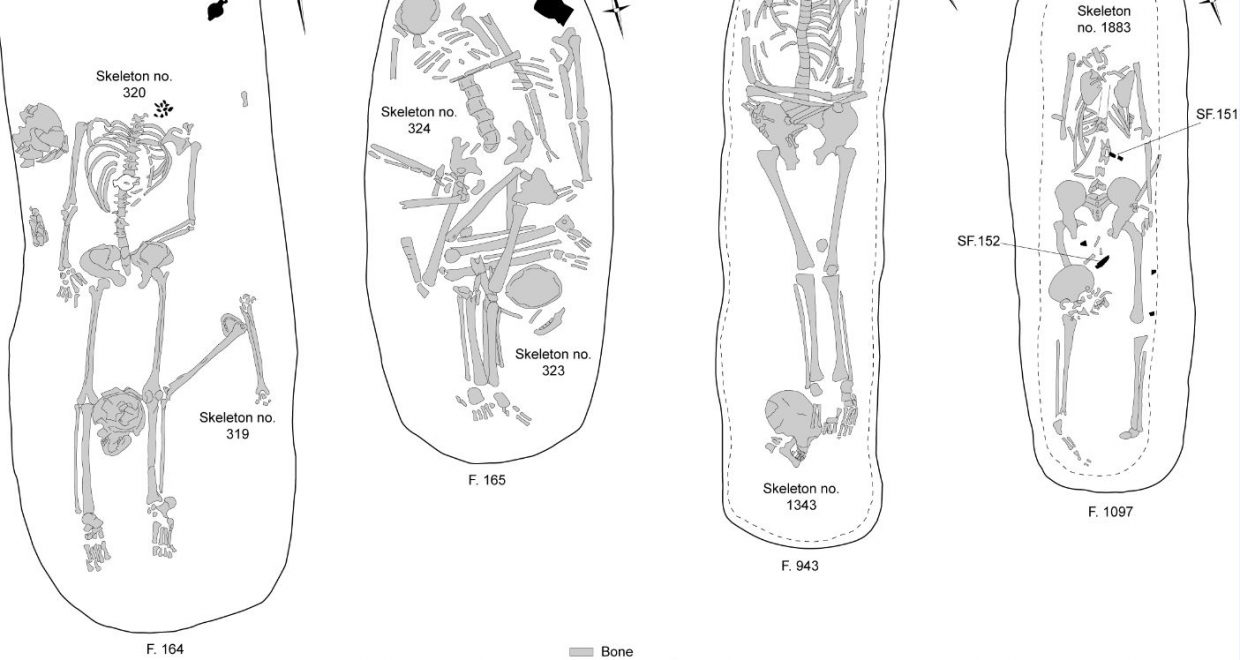

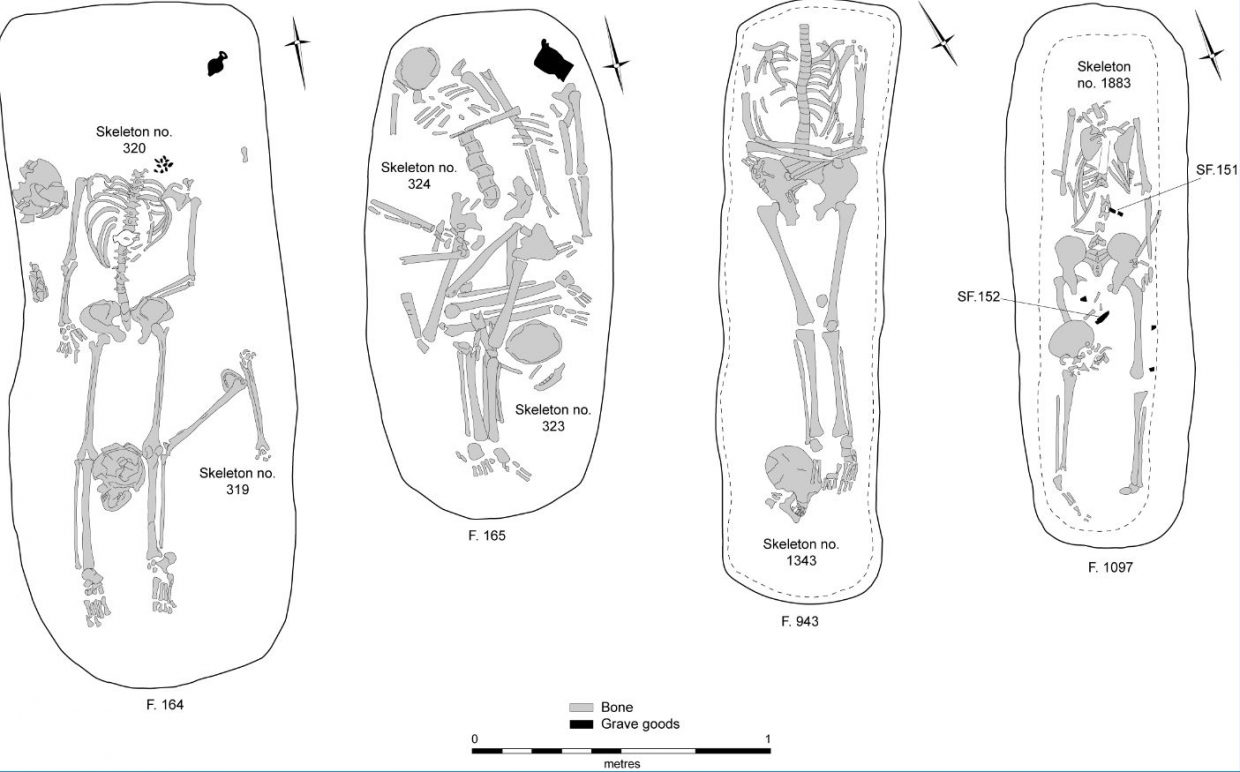

The victims were found in three small cemeteries which contained a total of 52 inhumation burials. The bodies had been buried around the margins of fields on the edges of a farm settlement: a common way of burying the dead in rural areas. Curiously, the decapitated bodies were distributed amongst the other regular burials, with nothing to mark them out as different from their neighbours.

Analysis of the bones by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit showed several of the dead were probably alive when beheaded, and their treatment was not part of a burial ritual. Two were likely kneeling when they were killed by a sword blow from behind. Another man had heavy sword blows to the back of the skull, presumably to immobilise him before he was beheaded. And a fourth woman had many fine cut marks to her face, arms and legs, possibly indicating her body had been mutilated as well as decapitated. If these people had been killed in a ritual of some kind, then it amounted to human sacrifice—a practice that was illegal in Roman law. A more plausible explanation of these deaths is that they were executions.

The clue to the large concentration of decapitated bodies at the site came from nearby excavations and the changing nature of Roman law during the late Empire. The farm appears to have been part of a larger complex supplying the Roman military with grain and meat. This would have placed the community under higher levels of official scrutiny than most rural settlements in Britain. During the third and fourth centuries, penalties under Roman law grew steadily harsher, driven by fears for state security and the need to ensure state finances—much of which went to the military. Sites which supplied the army would presumably have been under particular scrutiny and malfeasance would have been treated harshly. This would explain not only the high number of executions found at the site, but similarly high numbers in associated supply settlements nearby.

The archaeologists could not be certain whether use of judicial execution meant the individuals were killed legally or not: the legal system might have been used to dispose of individuals on trumped-up charges. It is also not impossible that draconian punishments were inflicted on a few to keep the remainder of the local community obedient. But whatever the motivation, the form of the decapitations suggest official involvement.

More details of the decapitated Romans and other burials are published in the open access article Extreme Justice: Decapitations and Prone Burials at Three Late Roman Cemeteries at Knobb’s Farm, Cambridgeshire – out now in Cambridge journal Britannia.