Lichenology – Past, Present and Future

In this post we talk to Prof. Robert Lücking, an Editor for The Lichenologist, who reflects not only on his recent review of lichenology over the past two decades, celebrating the period over which Peter Crittenden was Senior Editor, but also describes his own introduction to lichens, and what the future holds.

- When did you first start researching lichens, and what questions were you asking at the time?

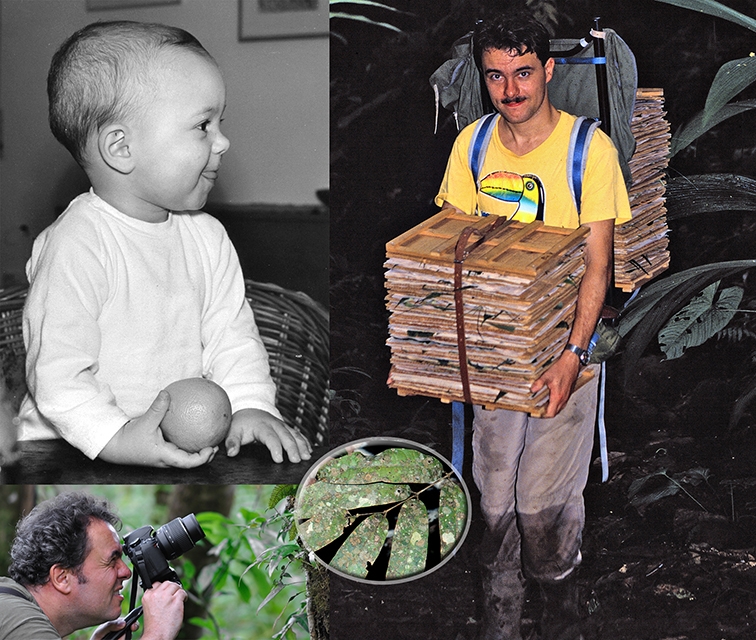

I came to lichenology through photography. When asked about my interests for a potential diploma thesis during a study year abroad in Costa Rica, I mentioned lichens, and my supervisor, the late Sieghard Winkler, proposed that I work with tropical foliicolous (leaf-dwelling) lichens, continuing his own, earlier studies on epiphylls in El Salvador and Colombia. Besides the taxonomy of these fascinating lichens, I quickly became interested in their ecology and in questions related to tropical biodiversity, using foliicolous lichens as a model group, as they allow experimental approaches due to their short generation times.

- Do you have a favourite lichenologist from history?

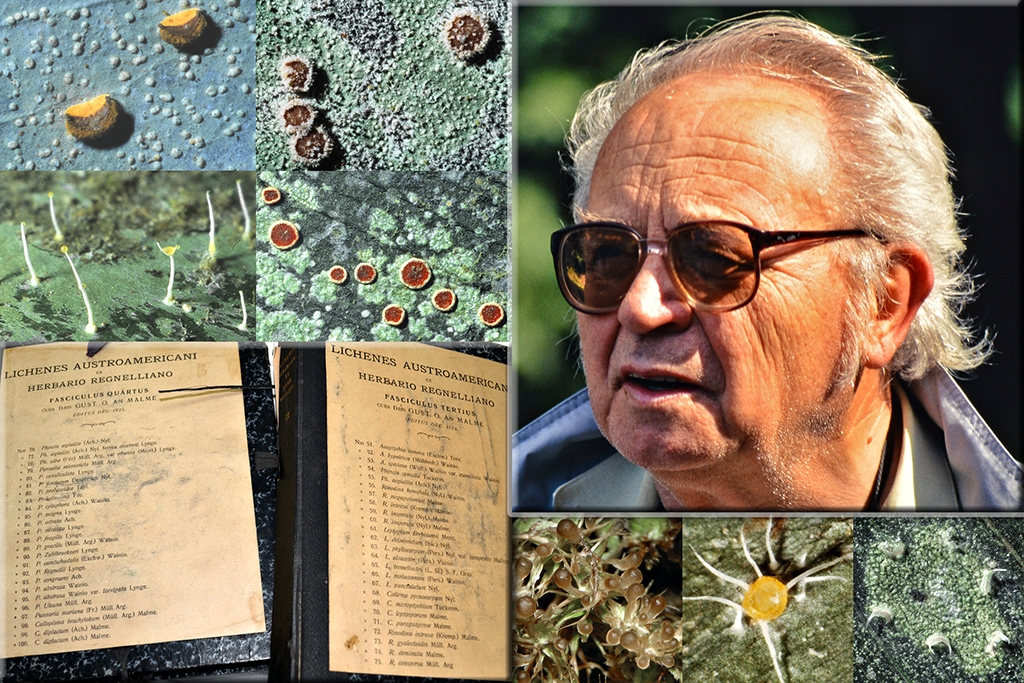

That has to be Antonín Vězda from the Czech Republic, who passed away in 2008 and who likely is the most eminent lichen taxonomist of the past century. It was him who helped me getting to know foliicolous lichens and I especially admired his keen eye, attention to detail, patience, and great drawing skills. Another, much esteemed mentor and colleague is the late Rolf Santesson, whose 1952 monograph on foliicolous lichens has paved the way for all subsequent work on this group. Going further back in history, I have also the Swedish lichenologist Gustav Malme on my list, a pioneer in modern taxonomy of tropical lichens and who was born exactly 100 years before me. Last but not least there is the Swiss botanist Johannes Müller Argoviensis, better known as “Müll. Arg.” Had I lived in the 19th century, he would likely have been my idol.

- You looked back over the past twenty years. What do you consider to have been the most significant changes in lichenology over that period?

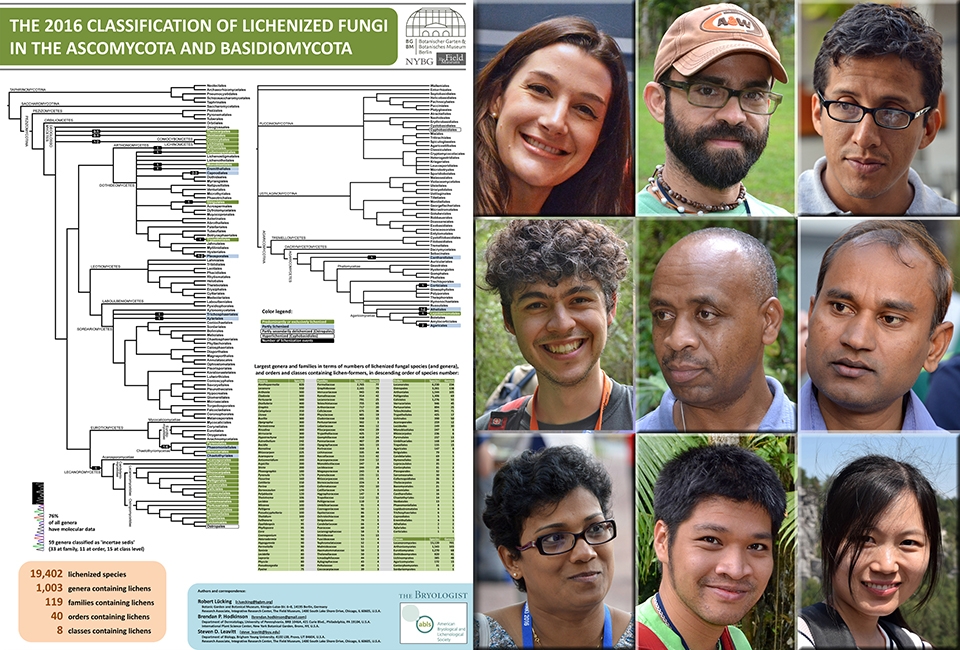

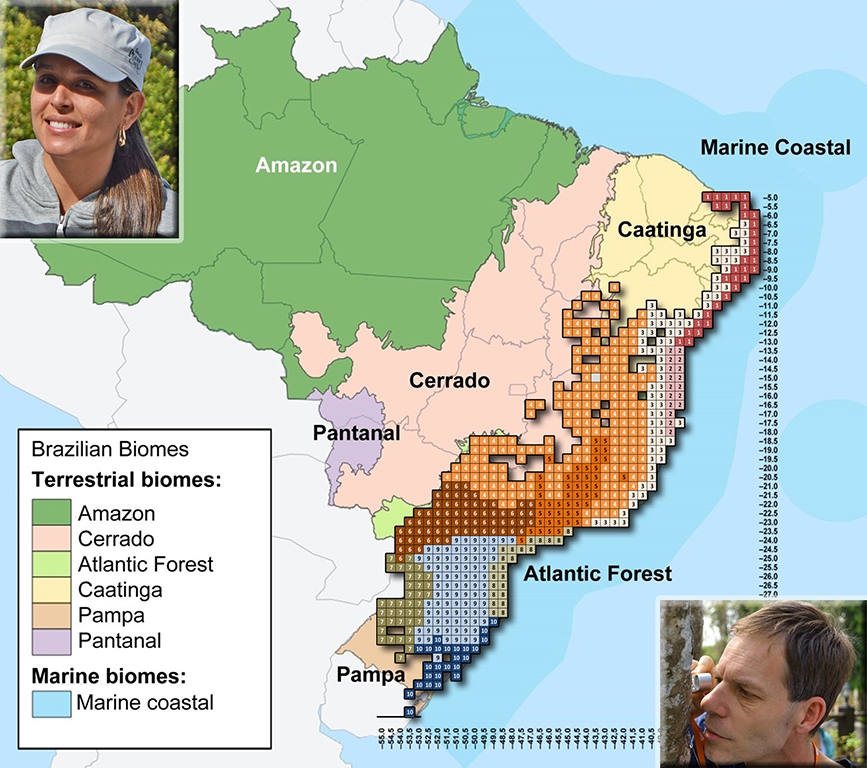

Certainly, and similar as in other groups of organisms, the advent of molecular phylogeny has shaped lichenology over the past two decades, giving us a much improved understanding of evolutionary relationships, species boundaries, and variation within species. We now have a rather solid foundation regarding the taxonomy and systematics of lichen fungi, although much remains to be studied and clarified. Other important trends were the increase of collaborative, cross-disciplinary and cross-continental approaches, the global expansion of high quality research in lichens including by colleagues in biodiversity-rich countries, and the growing prominence of lichen studies in high impact journals.

- Having reviewed the past twenty years, and considered past trends, can you anticipate what major questions or key developments might be over the next twenty years?

I would expect genomic approaches to become increasingly important to answer specific questions. Unlocking the secrets of the lichen symbiosis in relation to the lichen microbiome, as well as functional ecology, will be other advancing fields with many novel discoveries. On the other hand, new taxonomic discoveries and further improvements to the systematics of lichen fungi will continue at a rate similar to that of the past two decades. It will remain a challenge for journals and editors to maintain the balance between highly technical, methodology-driven studies and discovery-based biodiversity research, both equally important. Lichen-based biomonitoring will continue to play an important role in assessing the impact of climate change. With developing technologies, I further expect herbarium (fungarium) collections to become routinely incorporated in phylogenetic and genomic studies, opening a door to reconstruct the recent past.

- What advice would you have for young lichenologists, entering the field today?

I believe two aspects are important: a deep interest in the subject sparked by scientific curiosity, and perseverance in a highly competitive, narrow job market. For young lichenologists, I have five recommendations: (1) Get to know your lichens; it doesn’t matter in which area of lichenology you feel at home, a good taxonomic knowledge is an indispensable basis, and it will come in handy when in the field with colleagues. (2) Dominate a broad array of methods, especially bioinformatics; this is not only a key component of high-quality research but provides a competitive edge in the job market. (3) Never believe what anyone tells you (even if that person is an authority and most likely correct); always check for yourself: there is no better source than primary data. (4) Ask great questions and tell great stories; a good paper or presentation does not hinge on the latest methodology but whether a question is cleverly addressed and how you captivate your audience. (5) Be generous in sharing knowledge and data and give back what you received from others; there is more than enough work to be done and far too few expertise available.

Professor Robert Lücking’s article, “Peter D. Crittenden: meta-analysis of an exceptional two-decade tenure as senior editor of The Lichenologist, the flagship journal of lichenology“, published in volume 53, issue 1 of The Lichenologist, is available free for a month.