Prospects for better diagnosis of male genital schistosomiasis

The latest Paper of the Month for Parasitology is How can schistosome circulating antigen assays be best applied for diagnosing male genital schistosomiasis (MGS): an appraisal using exemplar MGS cases from a longitudinal cohort study among fishermen on the south shoreline of Lake Malawi

Our paper on diagnostics originates from my soon-to-be-completed PhD study that has focused on developing a better understanding of the interplay between schistosomiasis and HIV in Malawian fishermen. In my country, Malawi, schistosomiasis is well known especially along the shoreline of Lake Malawi, where through my professional medical duties and research studies, I have encountered many people seeking Praziquantel treatment. The disease, also known as Bilharzia and grouped within the neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), employs a preventative chemotherapy approach with praziquantel as its first foundation of disease control.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, schistosomiasis can be particularly common. Millions of young children, through to older adults, are affected by this disease, which may be life-threatening upon advanced disease progression like abdominal pain, blood or difficulties in passing urine, enlarged liver and spleen, liver fibrosis or bladder cancer. Schistosome infections are acquired through direct contact with freshwater sources that contain infective schistosome larvae, which penetrate the skin. Most often, daily activities such as bathing and swimming, or drawing water for domestic chores, places people of all ages at risk. Around Lake Malawi, adult men engaged in fishing are an especially well-known high-risk group, and having often had insufficient praziquantel treatment, have progressive disease.

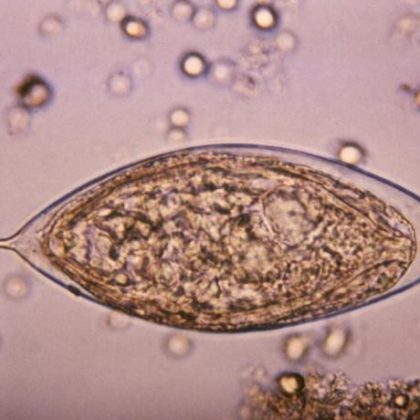

In Africa, Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni are responsible for the two forms of schistosomiasis: urogenital or intestinal, respectively. Accurate diagnosis of schistosomiasis in all its stages and forms remains a challenge despite scientific advances in general recognition of NTDs as a global public health concern. Several diagnostic methods for detection of urogenital schistosomiasis (UGS) have been developed over the years but we still do not have a reliable rapid point-of-care (POC) test. This is in contrast with intestinal schistosomiasis where a urine-based point of care circulating cathodic antigen (POC-CCA) strip assay test is commercially available and also advocated within WHO guidelines for disease mapping.

Although more efforts have been put into raising awareness in general, the treatment, control and prevention of schistosomiasis, and specific genital complications arising especially in male genital schistosomiasis (MGS) have been overlooked and underreported for decades. This perceived lack of interest has resulted in under-diagnosis, non-treatment and poor awareness in endemic areas; MGS is a gender-specific manifestation of schistosomiasis, associated with schistosome eggs and pathologies in genital fluids and organs most commonly observed with S. haematobium infection. This complication, first described in 1911 by Professor Madden in Egypt, causes genital or ejaculatory pain, abnormal ejaculates, infertility, enlarged organs, and tissue abnormalities observed on diagnostic examinations. Perhaps as the largest chronic parasitic public health burden in Africa, there is also a direct connection with HIV transmission as schistosome eggs in the genital tracts often are associated with raised viral loads in semen.

Unlike the recent advances in defining a clinical standard protocol for female genital schistosomiasis (FGS), MGS remains inadequately defined as there is no ‘gold-standard’ diagnostic test. Semen microscopy remains the recommended test for MGS, although its acceptability and applicability in endemic areas with limited laboratory capacity poses a significant challenge in the management of MGS. Urine filtration with microscopic examination for S. haematobium eggs has been utilised in such settings as a convenient but unfortunately error-prone proxy of MGS.

Through a recent longitudinal cohort study conducted among fishermen along the south shoreline of Lake Malawi in Mangochi district, my work described a novel low-cost sampling and direct visualisation method for enumeration of ova in semen, which helped to diagnose MGS, showing a prevalence of MGS was 10% using seminal microscopy and 27% on seminal real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), with UGS prevalence of 17%. With such diagnostic challenges regarding MGS highlighted, there is a need to improve diagnostic tests as well as to raise adequate professional awareness for comprehensive clinical assessment, treatment and inclusion of men in preventive chemotherapy programs like mass drug administration (MDA) campaigns with PZQ. I hope my paper on diagnostics draws attention to the importance of increased research on MGS diagnostics, and that an intricate knowledge on circulating schistosome glycans has application in better disease control.

The article How can schistosome circulating antigen assays be best applied for diagnosing male genital schistosomiasis (MGS): an appraisal using exemplar MGS cases from a longitudinal cohort study among fishermen on the south shoreline of Lake Malawi by S. A. Kayuni, P. L. A. M. Corstjens, E. J. LaCourse, K. E. Bartlett, J. Fawcett, A. Shaw, P. Makaula, F. Lampiao, L. Juziwelo, C. J. de Dood, P. T. Hoekstra, J. J. Verweij, P. D. C. Leutscher, G. J. van Dam, L. van Lieshout and J. R. Stothard is available Open Access.